As she lay dying, my paternal grandmother summoned me to her bedside. “Forgive me,” she said. For what, I had no idea. She remained lucid to the end, so she could not have mistaken me for my cousin Buddha, who was once caught stealing candles from the family store and for which stunt was deposited into a sack that Lola ordered hung from a beam in the kitchen. It was a riot.

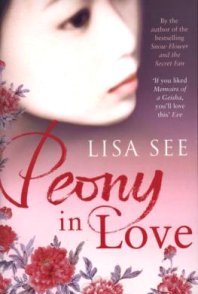

My lola was part Chinese, so I hope she’s in a far better place than the one Lisa See’s titular character finds herself in. In See’s take on the Chinese afterlife, ghosts roam and go hungry, ancient enmities fester, bureaucrats are on the take, and the lovelorn mope. It’s a lot like the living world, actually, except that a ghost can chill a room with its presence, lurk in dreams, and channel thoughts to the living. For all that, it cannot navigate sharp corners, though that can’t be much of an obstacle if you can also fly, but there you are.

The story takes us back in time to 17th-century Qing Dynasty China. We meet Peony two days before she turns 16; she is pretty, smart, and the apple of her father’s eye. She is also engaged to be married to a man she has not seen, a fate she accepts to be her filial duty, although this does not stop her from fantasizing of finding True Love — the fuel for this fantasy being a book of an opera she hasn’t seen about love so powerful that it defies logic (the heroine, Liniang, and her lover only meet in dreams), reason (she dies of lovesickness), and death (his love brings her back to life).

Then one night Peony meets a handsome stranger — a poet, no less. She is convinced that he’s the man of her dreams, her One True Love, but what’s a dutiful daughter to do? So she finds consolation in her favorite book, imagining herself in the role of the doomed Liniang until she, too, wastes away and dies. Stupid girl, you think; doesn’t she realize that that stranger is probably her soon-to-be husband? And don’t you know it: he is.

I’m not doing you a disservice by revealing that particular plot point, by the way (it says as much on the back cover). Yes, Peony falls for that dreck and she gets plenty of time to regret it once her spirit goes flying off into the ether. Being dead, you see, is bad enough. But being single, Chinese and female compounds the problem: Peony finds that SCFs have no juice in the afterlife, which is no incentive for living relatives to honor their memory. Say what you will about the Chinese, but they’re never impractical. To top it all off, a small oversight causes Peony’s spirit to wander the earth as a hungry ghost, and you’re forgiven for suspecting that the way out of this predicament somehow involves a journey to resolve the business she left unfinished in the realm of the living.

But doesn’t it always? Along the way Peony meets other lovesick maidens, rancorous ancestors, flesh-eating dogs, and her own grandmother, who lets Peony in on some terrible family secrets and has a thing or two to say about men and their ways, but is wise enough to let her granddaughter figure things out on her own. The narrative surges forward several years and goes back generations. In the interim, Peony authors a commentary on her beloved book (with her sister-wives), helps conceive and birth a child while she dodges swords and mirrors, and learns a great deal about love in its various incarnations. Apparently there is no rest for the Chinese dead.

Still. The afterlife in Peony in Love is by turns disappointing and reassuring. There’s no comfort in being told that death does not rid us of our emotional baggage nor frees us from the restraints of our roles in society; that a word said out of turn can still wound, or that we will still yearn as much and as painfully as when alive. But then we are also left with possibilities: to change our minds, to right wrongs, to forgive and be forgiven in return, and to find love in the strangest places. I think that’s cool. If Lola is indeed hovering over me right now, amused that I still remember the candle-and-sack incident, I hereby take this opportunity to tell her that, as far as I’m concerned, she has absolutely nothing to be remorseful about. If anything, I’m glad it wasn’t me inside that sack. Cousin Buddha, you see — he had an accomplice…

(In memory of Hilda P. Layug, who left too soon to ever become a mother, but is missed by those whose lives she graced as daughter, sister, and friend.)

This post has no comments.

Post a Comment